UNSOLVED

The “Highway of Tears” is the colloquial name given to a 725-kilometer stretch of Highway 16 in British Columbia, Canada, where dozens of Indigenous women and girls have disappeared or been found murdered since the late 1960s. Spanning between Prince George and Prince Rupert, this scenic route winds through rural and often remote landscapes, which have become symbolic of one of Canada’s most chilling and unresolved mysteries.

As authorities and advocates struggle to uncover the truth, the question remains: Is there a single “Highway of Tears Killer,” or are multiple predators responsible for the ongoing tragedy?

Historical Background and the Victims

The disappearances and murders along the Highway of Tears have disproportionately affected Indigenous women and girls, a fact that is tied to systemic racism, social inequality, and the vulnerability of Indigenous populations in Canada. Many of these women were hitchhiking due to the lack of affordable public transportation and the remoteness of their communities.

Since 1969, more than 40 women and girls have vanished or been murdered along the highway, though some estimates put the number significantly higher. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) initially acknowledged 18 cases between 1969 and 2006, but local Indigenous groups and human rights activists argue that this number is far too low, suggesting that up to 80 women might have been victims along the broader Highway 16 corridor and surrounding routes.

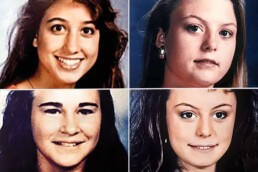

Profiles of the Victims

The victims have primarily been young women, most between their teens and twenties, and many were last seen walking or hitchhiking. While there are a few instances of older women, the pattern that emerges is one of youth, marginalization, and vulnerability. The majority of these women come from Indigenous communities, where the poverty rate is higher, resources are fewer, and transportation options are often nonexistent.

Here are the cases tied to the Highway of Tears:

List of Recognized Victims of the Highway of Tears

- Melanie Karina M. Thomas (2000)

- Tina Louise M. Lavoie (2001)

- Darlene Marie K. McKay (1973)

- Tamara K. Chichak (2001)

- Rochelle Elizabeth H. Thomas (1995)

- Angela T. K. Kater (2005)

- Tina D. Henry (2001)

- Cynthia L. (Cindy) Williams (1978)

- Ramona Mary Wilson (1994)

- Colleen MacMillen (1974)

- Alberta Williams (1989)

- Nicole Lee Hoare (1994)

- Mary Anne G. McKenzie (1978)

- Aielah Saric Auger (2006)

- Yvonne N. B. U. (Megan) J. Joseph (1995)

- Beverly Marie F. W. (Bev) M. P. B. (1994)

- Marie M. A. M. J. (Mari) W. (1994)

- Shirley C. H. R. C. (Shirley) A. (1979)

- Joyce C. S. (Joy) H. P. (2000)

- Gina Mary S. (Gina) W. (1996)

- Kira S. (Kira) L. P. S. (1999)

- Shelley Lynn L. (Shelley) H. (2004)

- Lindsay A. R. (Lindsay) C. M. (2004)

- Angela L. (Angela) B. (2004)

- Heather T. S. (Heather) H. (2001)

- Teresa B. (Teresa) D. (2001)

- Darcie N. K. (Darcie) R. (2000)

- Pamela E. (Pam) K. (2004)

- Ava M. C. (Ava) B. (1994)

- Tanya K. (Tanya) J. (1995)

The Search for the Killer(s)

For decades, families and communities have been asking the same question: Is there one killer or several responsible for the violence along the Highway of Tears? The answer remains unclear.

The RCMP launched several investigations into these cases, the most significant being the “Project E-PANA” task force, established in 2005. The goal of E-PANA was to investigate the deaths and disappearances of women along three key highways in British Columbia, including Highway 16.

This task force examined whether a serial killer could be at work. However, despite these efforts, no single individual has been conclusively identified as “the Highway of Tears Killer.”

There have been some notable suspects and arrests, but nothing that links all the cases together.

Notable Suspects

Bobby Jack Fowler: One of the few named suspects in connection to the Highway of Tears cases, Fowler was an American drifter with a history of violence against women. In 2012, DNA evidence linked him to the 1974 murder of Colleen MacMillen, a 16-year-old girl last seen hitchhiking along Highway 16. Fowler, who died in prison in 2006, is believed to have been in British Columbia around the time of several other disappearances. However, investigators could not definitively connect him to all the Highway of Tears cases.

Cody Legebokoff: Convicted of the murders of four women, Legebokoff, one of Canada’s youngest serial killers, was arrested in 2010. While his killings took place in Northern British Columbia, his known victims were not hitchhiking and their circumstances differed from those of the women along Highway 16. Nevertheless, his crimes heightened fears that multiple predators might be operating in the same area.

The Indigenous community has long accused Canadian authorities of systemic racism and neglect in their handling of the Highway of Tears cases. Many of these women were dismissed by law enforcement, and their disappearances were not immediately treated as urgent.

The lack of initial response led to critical delays in investigating, collecting evidence, and providing closure for the families of the victims. The systemic issues affecting Indigenous women extend beyond just the Highway of Tears.

They reflect a broader national crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG). According to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Indigenous women are more likely to experience violence, be murdered, or go missing compared to non-Indigenous women.

Why the Highway of Tears?

There are several factors that make the Highway of Tears particularly dangerous for vulnerable women:

Remote Locations: The highway passes through vast stretches of forested and mountainous terrain, much of which is sparsely populated. The isolation makes it difficult for witnesses to come forward or for anyone to intervene in real-time.

Lack of Public Transportation

Many of the small communities along the highway have little or no access to public transportation. Hitchhiking became a common mode of travel for many residents, particularly for young women who lacked the financial means to own a car or pay for rides.

Economic Disparities

High levels of poverty in these regions mean that Indigenous women often face barriers to education, employment, and health services, leaving them more vulnerable to predatory behavior.

Recent Developments and Ongoing Advocacy

In recent years, the cases along the Highway of Tears have garnered increasing national and international attention. Families and advocacy groups have worked tirelessly to bring attention to the issue, leading to inquiries, investigations, and national movements like “Walking with Our Sisters” and the Red Dress Campaign, which honors the missing and murdered Indigenous women.

In 2015, the Canadian government announced a national inquiry into MMIWG, which concluded in 2019. The report declared the murders and disappearances a “Canadian genocide” and made sweeping recommendations to address the systemic factors that have led to such widespread violence against Indigenous women.

Additionally, some progress has been made in the form of increased safety measures along Highway 16. For example, there has been the implementation of a bus service designed to provide safer transportation options for residents traveling along the route, especially for women who would otherwise resort to hitchhiking.

The Legacy of the Highway of Tears

While some suspects have been identified, most of the cases remain unsolved, leaving families without answers and communities still grappling with loss. The Highway of Tears represents not just a physical journey through the wilderness but also a stark reminder of how society can fail its most vulnerable members.

The question of whether the Highway of Tears is haunted by a single serial killer or the actions of multiple predators remains an enduring enigma. In their names, the journey for truth continues.